What is the FIFO method, and how can you use it to measure your ecommerce firm’s financial efficiency? Are there alternative methods worth considering?

Key takeaways

- FIFO inventory valuation assumes oldest stock sells first, helping ecommerce owners calculate accurate cost of goods sold.

- Calculate COGS by adding starting inventory and new purchases, then subtracting ending inventory value.

- FIFO typically shows higher profits during inflation since it lists earlier-purchased, cheaper inventory first.

Do you own an online store? You are well-positioned to take advantage of the ecommerce scene’s continuing growth. However, it’s important that you monitor your online store’s inventory lest your cash flow is disrupted.

As you know, there are many costs involved in running an ecommerce business — including sourcing the products it will stock. Using the FIFO method, you can quickly and easily calculate the net income you make from selling goods.

The acronym FIFO means “first in, first out” — the principle of selling your oldest stock first. Many ecommerce entrepreneurs handle their inventory in this way as a matter of course.

So, should you use the FIFO method formula? If so, how?

What is the FIFO inventory method?

As mentioned just above, you can use a ‘FIFO method’ when deciding which of your stock you ought to ship out first. Often, though, when people use the term ‘FIFO method’, they are referring to an inventory valuation technique.

Whether your oldest stock is the stock that does ship first is largely irrelevant to the question of whether you should use this accountancy procedure. The FIFO method simply assumes that your inventory is being handled in this fashion. Put simply, the FIFO method assumes that the goods that were purchased or produced first and sold or removed first.

However, in reality, when a customer places an order for a product, age won’t be the only factor behind which specific unit is chosen for delivery.

Just think about how certain tech hardware tends to be periodically ‘refreshed’ — without necessarily any big change in the product name. Apple brought out a 7th-generation version of its iPad mini tablet in October 2024. However, publicity materials for this new device do not draw major attention to its generation number.

In late October, many online stores would have continued to offer leftover units of the just-discontinued 6th-generation iPad mini. However, these units could have taken a while to sell while tech-savvy customers were rushing to buy the new model.

So, depending on the product, newer units might sometimes be prioritized for delivery to customers. Still, FIFO is a widely accepted method of calculating inventory value for accounting purposes.

How the FIFO method formula works

Let’s imagine that, during the accounting period, you inherited one batch of inventory (‘Batch A’) left over from the preceding period. This would be your starting inventory.

For the sake of argument, let’s say that your starting inventory comprised 50 units you acquired for $10 each. During the subsequent accounting period, you may have ordered a further 200 units (‘Batch B’) of this starting-inventory product. However, by that point, inflation could have increased the per-unit price to $15.

Looking at your sales figures now, you might realise that you sold 140 units of this product overall during the period. Using the FIFO inventory method, you would assume that you shifted all 50 units of Batch A before you started depleting Batch B. (Whether this actually was the pattern of your inventory movements is of no consequence when using the FIFO method correctly.)

To value your inventory the FIFO way, you would first multiply the number of Batch A units by the value attached to them above. This means 50 x $10 = $500.

Since you sold 140 units of this product overall in the period, you would assume that the remaining 90 of them came from Batch B. When calculating the total worth of these Batch B units (including the unsold ones), you use the inflated per-unit price of $15. This entails making a sum of 200 x $15 = $3,000.

The ending inventory is the stock you are left with as the accounting period elapses — so, in this case, 110 units of Batch B. Hence, the sum you must use to figure out the ending inventory’s value is 110 x $15 = $1,650.

Now add the starting inventory’s cost ($500) to the cost of buying fresh inventory ($3,000). This gives you $3,500. Subtract the ending inventory’s cost ($1,650) from this, and you get $1,830. This is your cost of goods sold (COGS) for the accounting period — when you use the FIFO method correctly, anyway.

What is ‘cost of goods sold’ (COGS)?

One strong incentive to use the FIFO method is that, due to inflation, products tend to become pricier to source over time. So, by listing earlier-acquired products first on an income statement, you can generally log higher profits.

Naturally, you should aim to make sure you sell your products at a higher price than you pay for them. Otherwise, you could struggle to break even and turn a profit.

This is why you must pay particularly strong attention to the metric “cost of goods sold” on your business income statement. It’s not hard to locate this data (often referred to as “COGS”) on the income statement, as it’s always on the second line.

It is crucial data. You need to use it to calculate your company’s gross profit. To find this figure, you subtract your COGS from your revenue.

Anyway, let’s get to the point — what is COGS? It’s the price you pay to procure or produce what your business sells.

COGS is not to be confused with operating expenses, despite the latter also being factored in when calculating profit. While COGS refers to direct costs of producing or obtaining stock you sell, operating expenses are indirect costs of running the business. Operating expenses include:

- Rent

- Employee salaries

- Insurance

- Marketing campaigns

None of these operating expenses are directly tied to any particular products you sell. Instead, they focus more on the bigger picture of how your business is getting by from day to day. Even marketing campaigns typically focus on multiple products.

Looking for more information? Check out our guide to Cost of Goods Sold: Definition, formula, and examples.

How to lower your COGS

One problem with selling physical products is how much they can push up your COGS. These products can be expensive to make due to the many different parts you would need to source for them.

Opting to only sell physical products made by other people or companies is not necessarily a cost-effective alternative, either. These third parties will be shouldering the manufacturing costs and so want to recover them from sellers like you.

This all begins to hint at the financial appeal of selling digital products. A digital product — like an ebook, digital artwork, or online course — only has to be created once before you can start selling it.

Plus, no matter how many customers buy and download it, there’s no danger of it going “out of stock”. So, you can effortlessly keep up with demand and sit back and relax while watching the money roll in.

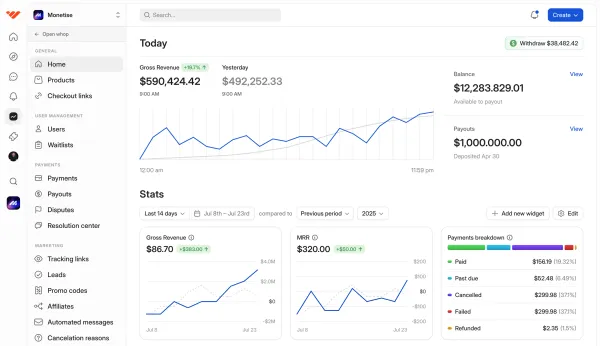

You can even sell digital products for free by joining an online platform suited to the purpose, such as Whop. Here, creators can take just minutes to set up their own online shops known as ‘whops’. Here’s a complete guide to whops…

When might you want to pivot to digital products? After calculating COGS for your physical products, you could find that many of them make you only slightly more money than they cost you. Some of them could even be losing you money.

In sharp contrast, digital products can cost virtually nothing (or very little) to produce. For example, if you love reading, you might already have the necessary expertise to write your own ebooks. Even if you don’t, writing experts on Whop could help you to hone your skills.

Dive into the Discover tab on Whop to search for whops equipped to assist you with your ecommerce endeavors. Between them, the whops here touch upon many different subjects relevant to online entrepreneurs, from travel to fitness.

How to calculate your COGS

You would usually do this at the end of each accounting period — whether that’s monthly, quarterly, or annually.

If you get through a lot of inventory, you could opt to calculate your company’s COGS even more often than monthly. Doing so can help you to more precisely measure your profit vs revenue.

To calculate your COGS for a given period, you typically need to know what you spent on all of the following…

- Your starting inventory: How much did you spend on the inventory you started the period with? This is inventory you originally got hold of earlier but failed to sell before the period you are now assessing.

- Buying or manufacturing new inventory: This point is rather self-explanatory, but yes, you are now looking at the money you spent specifically for either purpose (or both) during the period.

- Your ending inventory: What did you spend on the inventory your online shop was left with come the end of the period? This ‘ending inventory’, as it is called, can be rolled over to the next period, becoming its ‘starting inventory’.

Once you’ve got the figures for the above three components, you can use this formula to calculate COGS:

Cost of starting inventory + Cost of buying or manufacturing new inventory - Cost of ending inventory

How might this work in practice? Let’s look at two hypothetical examples…

Example 1

At the end of 2023’s fourth financial quarter (running from July 1 to September 30), an electronics retailer is left with $10,000 of inventory. Much of this inventory was of a much-hyped gadget only released toward the end of the quarter.

So, the business owner is optimistic about the next quarter’s sales and consequently decides to order $25,000 of inventory for it. Sales could indeed go relatively well, leaving the company with $2,000 of inventory as the quarter elapses.

In this scenario, the quarterly COGS calculation would be:

$10,000 + $25,000 - $2,000 = $33,000 (the cost of goods sold)

Example 2

Running a business is risky for a first-timer. In fact, entrepreneurship statistics show 20% of new businesses failing within their first two years and 45% within five years.

It’s therefore easy to imagine a situation where someone owning a small business checks its COGS monthly rather than quarterly or yearly.

A startup could start a month with $2,000 of inventory and, out of caution, spend only another $4,000 on inventory before the month is out. This conservatism could prove warranted, with $1,000 of inventory left for the business at the month’s end.

Here is how the business owner would calculate COGS for that month:

$2,000 + $4,000 - $1,000 = $5,000 (the cost of goods sold)

Before using the COGS formula for your own business, though, you might wonder how exactly you ought to value your inventory.

Different products can vary widely in price, as can multiple units of the same product, e.g. due to limited-time discounts. Do you really have to note down all the individual prices of every single product you sell? Not for accounting purposes, thankfully!

Nonetheless, the inventory valuation process you choose is no small concern, as it determines what COGS figure you reach.

FIFO vs. other ways to calculate COGS

As each inventory valuation technique has its own merits and drawbacks, you could initially struggle to discern which method would best meet your specific needs. However, on closer inspection, some of them could turn out not to be practically viable for your particular company.

FIFO vs. LIFO

The acronym here stands for “last in, first out”, which does a lot to explain how you use the LIFO method. You start by assuming that the inventory you bought first is also the inventory you prioritized sending out to customers.

Let’s return to the scenario used to explain the FIFO method formula. You entered the accounting period with 50 units of the product bought for $10 each. This is Batch A. A further 200 units of the product were ordered during the accounting period at $15 apiece. This is Batch B.

As you might recall, a total of 140 units were sold. Under the LIFO system, you would assume that all of these units were taken from Batch B, with Batch A left untouched.

So, to calculate COGS with the LIFO approach in this scenario, you can simply multiply $15 by 140. This would give you $2,100.

This COGS figure is noticeably higher than the $1,830 reached with FIFO. LIFO does often fetch higher COGS figures, as it places greater weight on newer (and, due to inflation, usually pricier) units.

In the above scenario, things would get a bit more complicated if you had instead sold 220 units. With LIFO, the assumption would be that you used up all of Batch B’s 200 units before dipping into Batch A for the remaining 20.

The total worth of Batch B is $3,000. So, the next step is to calculate the value of the other 20 units, using the sum $10 x 20 = $200. Now just add $3000 and $200 to get $3,200, your COGS under LIFO.

By using LIFO, you can be left with lower profit figures. However, these could lead your business to be placed into a lower tax bracket, consequently saving you money.

FIFO vs. average cost inventory

Otherwise known as the weighted average cost method, this involves calculating the average cost of each inventory unit available for sale during the period.

How would you apply this method to the two batches mentioned above? The 50 Batch A units cost $500 altogether, while the 200 Batch B units are valued at a collective $3,000.

Overall, you had 250 units worth $3,500 in total. So, you would divide the latter by the former, valuing each inventory unit at $14.

The average cost method is easier to use than FIFO. However, the former remains best for brands selling goods unlikely to become increasingly expensive to buy or make. Otherwise, it would be wiser for you to stick with FIFO, as it can help you to depict your company as financially flourishing.

FIFO vs. specific inventory tracing

You might sometimes see specific inventory tracing described as special identification. This is where you record the value of each individual piece of stock you bring in. You then calculate the overall worth of your inventory by adding all the individual values together.

This approach isn’t practical for many large firms. Hence, it is typically reserved for small companies selling a small number of highly unique pieces.

Specific inventory tracing can really come into its own when you are reselling on a second-hand marketplace such as Vinted.

Conversely, if you specialize in selling large numbers of mass-produced items, you are better off using FIFO. It would let you calculate your COGS much more quickly.

Pros of FIFO

It’s worth carefully weighing up the pros and cons of FIFO before deciding whether to opt for this particular method. However, there are several good reasons why FIFO has become widely adopted across the world…

Follows the natural flow of inventory (a lot of the time)

Oftentimes, the stock a business gets first is the stock that is also sold first. Perishable goods fall into this category, as can ‘trendy’ products you could be eager to shift before the iron goes cold. Remember the ‘fidget spinner’ craze of 2017?

Even with some supposedly ‘evergreen’ products, the safest bet can be to offload the oldest units first. Some could be in a design that looks neutral now but comes to be seen as ‘outdated’ sooner than you had expected.

So, delivering older inventory first can prevent you later having to write it off. Using FIFO can also place higher value on your ending inventory. This can have positive financial implications by making you less inclined to write off the leftover stock.

Easy to understand

Exactly because FIFO reflects how your inventory is likely to move, it can also be the easiest inventory valuation method to understand.

What counts as ‘starting inventory’ under FIFO would actually be touched last under LIFO. So, attempting to adjust the usual COGS formula for LIFO can throw up lots of frustrations. Admittedly, though, even getting to grips with FIFO isn’t always simple…

Higher net income

As this article has established, COGS figures tend to be lower when the FIFO method is used. As a result, inventory costs — at least on paper — eat less extensively into your revenue. Hence, FIFO enables you to record higher net income.

This can bode well when you insert your FIFO-derived profit figures into an ecommerce business plan. Being able to show these higher figures to investors can help you to woo them and secure their financial support.

If these are major objectives for you, be sure to assemble your business plan in a format approved by the Small Business Administration (SBA). Bplans offers a free small business plan template adhering to this specification.

This Bplans document is one of many business plan templates you could benefit from during your entrepreneurial journey. With each of these options, it’s just a matter of downloading the template and then filling in the spaces with your corporate details.

Widely accepted by tax authorities

Considering using LIFO? Keep in mind that, in most countries, its use is banned by the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

LIFO is still permitted under the United States’ Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS) — and, for that matter, actually practiced in the US.

What if you run your online store outside of the US? Sticking to FIFO can help you to avoid your business being investigated by tax authorities. Imagine the negative publicity you could end up attracting otherwise…

Cons of FIFO

These disadvantages could prove to be minor inconveniences, not enough to deter you from implementing FIFO. In other, limited circumstances, you might need to seriously consider switching to alternative means of valuing inventory.

Financial risk

FIFO can paint a misleading picture of your company’s financial health. If you regularly order certain items that suddenly soar in price toward the end of the accounting period, FIFO could dangerously understate your expenses.

If your financial margins have recently gotten perilously thin or even been wiped out, your FIFO-derived COGS figures might not show it.

Higher taxes

Yes, FIFO can represent your company as highly profitable. However, one downside of this is that you could be hit with heftier taxes as a result.

Should your own business use the FIFO method?

Some units in your online store’s stock could fade in quality the longer you keep them. Perishable foods can become unsafe to eat, while clothes can go out of style.

Do you sell any items like these? If so, using the FIFO method can guard against the risk of having to write off inventory rendered unsellable due to age. You just can’t be certain how quickly you will be able to empty your inventory.

Level-up your ecommerce game with Whop

Running your own ecommerce store can be extremely rewarding - but it's difficult to know how and where to start.

Whop is here to help.

Whop is home to thousands of online courses and communities - including those that focus on ecommerce advice and education. Whether you're selling digital or physical products, looking for help with marketing or manufacturing, you can learn from the pros on Whop.

With Whop you get more than a static stand-alone course. Whop is home to thousands of whops - online hubs that can incorporate chat streams, video calls, courses, files, and more. Each whop has it's own structure so you can choose the right one for you.

So head to the Whop Discover page to find an ecommerce group for you. Whether you're looking for a self-guided course, pro-mastermind, beginner's webinar or one-on-one coaching, you can find it all on Whop.